Experimenting with free range and pasture raised models

As a regenerative farm, raising animals on pasture fits with many of our values - all activities are to improve soil. Pasture raised systems are modular, mobile, and management intensive (3 M’s) - modular meaning they can be scaled up or down with minimal change and effort, mobile meaning animals are always moving and there is no fixed infrastructure, and management intensive, as a result of being mobile and trading the technology often associated with fixed infrastructure for man power. By animals always being on the move, they are grazing and trampling grass resulting in a layer of organic matter developing over the soil that protects the microbiology of soil, decomposes to improve the organic matter component of soil, and therefore improve water retention with the ultimate aim of creating a a resilient, diverse landscape.

Pasture raised models are also high welfare models because the animals have unlimited access to the outdoors, constantly moving means they have hygienic living conditions avoiding the need for routine antibiotics by breaking pathogen cycles, and plenty of space. The chickens only need a simple shelter or pen. Because animals are outdoors 24/7, in winter this can be problematic in a colder climate, unless precautions are taken. Ours are raised with a shelter, surrounded by an electro-net, so they are not enclosed in a pen at any time but their impact is managed thanks to the electro-net, and they are protected from predators.

(click pics to see more)

THE WHY

Usually in winter we stop our pasture raised chickens for a month or two. However, this year we decided to give it a try and continue through winter to ensure we can supply a consistent market. It was important though that the animals were still well cared for, and this required some planning. Being on a slope, we could have issues with chickens huddling for warmth and slipping down the hill, ending up in a big pile at the bottom of the shelter which can cause injury and suffocation. In summer this is not a problem because we can raise the shelters to allow air flow. and free movement. For winter, we decided to try a ‘step down' brooder’ approach by moving the chickens out into a shed, where we could use heat lamps at night, and outdoors during the day. This is more like a free range style of raising chickens.

We wanted to see if this would help the chickens acclimatise better before moving out into field shelters. To still make this an environmentally positive exercise, we decided to put the chickens to work, making compost in the shed, for spring planting, while they were there! (We are suckers for still doubling down on every task!) The difference is, that we will not be using this set up for batch after batch of chickens. It was used for two entire batches of chickens with the purpose of building compost, and then possibly it would be used as a ‘step-down’ brooder for only a short time to give the chickens time to acclimatise during the winter months. It was such a good learning experience so we decided to share our thoughts.

THE HOW

We start our process, as usual, with buying in Day Old chicks from a small, local hatchery. Our solution for the new chicks in winter was a box brooder. This is something we had not used before so it came with its challenges of ensuring chicks were warm but not too hot. The first week in the brooder is critical. Any issues at this stage can lead to pneumonia and other respiratory issues, as well as organ development problems that only show up much later on once the chicken has been fed for weeks. This has helped keep the temperature of the brooder up despite the plummeting ambient temperatures. Chicks are kept in the brooder until they have lost their soft yellow down and are feathered out with their white, warm adult feathers.

The first two pictures below show our summer brooder, and the second two show the box brooder with a ceiling to trap warmth from the lights and body heat of the chicks.

(click pics to see more)

The second hurdle was when the chickens were due to move from the brooder out onto pasture. Moving from brooder to the outside is always tricky, and despite phased cooling of the brooder, it is still a shock to the chickens and has to be managed carefully. The move from 32C at the beginning down to ambient temperature in summer is more easily managed than in winter when the temperature variation is much greater. We usually begin by turning brooder lights off during the day for a few days, then off day and night, and then keeping windows open to let cooler air in during the day.

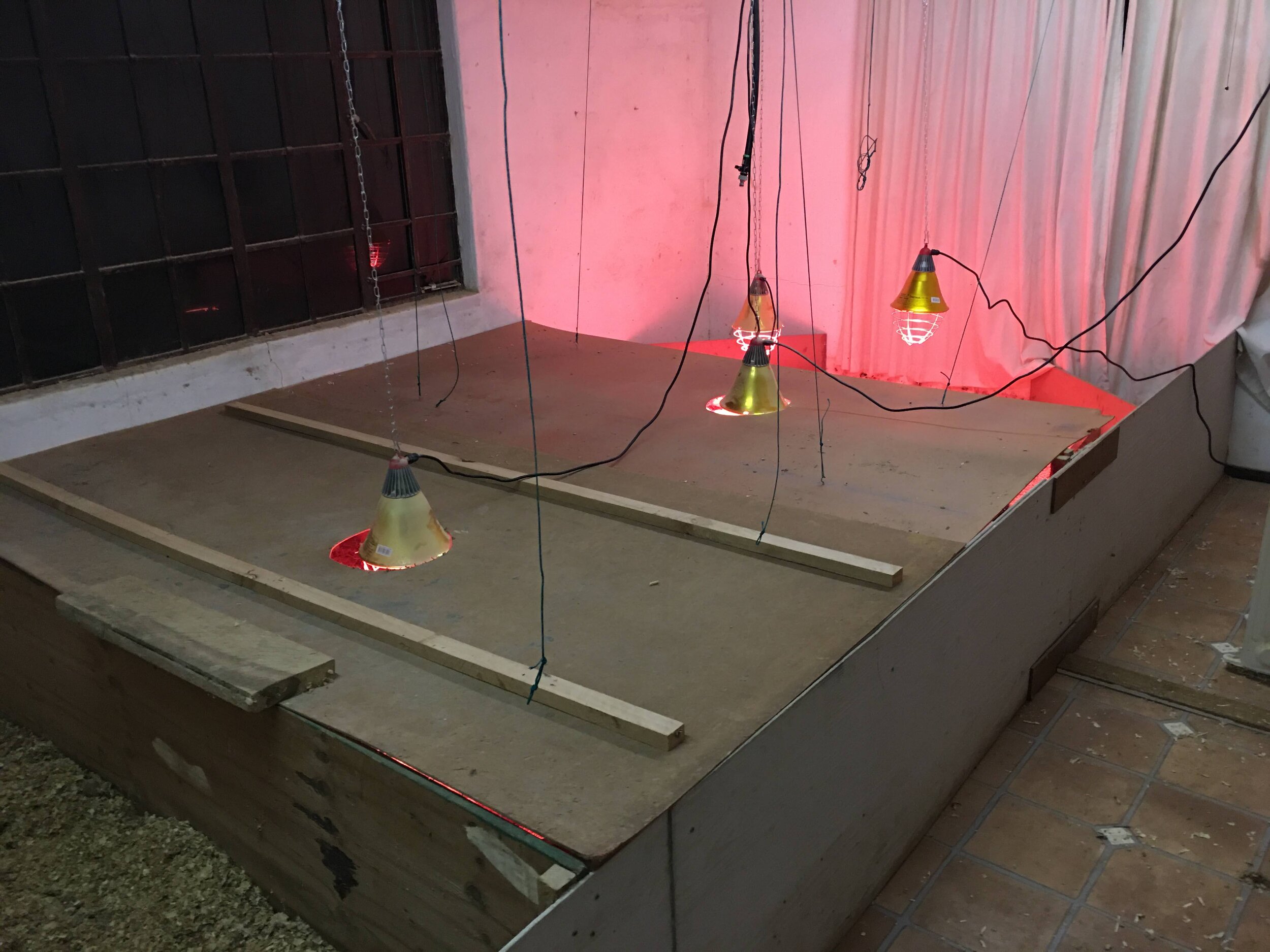

To help this process, we converted a three sided shed into a ‘step-down brooder’/ free range style. The shed had three walls of brick, about three quarters of the height of the roof so there was a nice ventilation space between where the walls ended and the roof started. This was secured from owls with shade cloth that still allowed airflow. On the fourth side we hung heavy shade cloth curtains, floor to ceiling that were opened up during the day to let the chickens out on to the grass. At night we brought them back in. This meant going from a warm brooder to a more outdoor style, but with nighttime warmth, to assist in the phased acclimatisation. At the same time, it gave us an experience of a free range operation for comparison.

(click pics to see more)

Compost Chickens

(click pics to see more)

We hired a wood chipper and chipped a whole lot of wood into the shed area and it began breaking down a few days before the chickens moved in. This created warmth from the floor. When the chickens joined the party, their manure added to the wood chips and further accelerated the decomposition. Daily we added shavings to keep the chickens dry, and turned the litter. It produced a lot of warmth. So our compost chickens were raised in a more free range style which was a fantastic experiment for us, the chickens were warmer, and we got a whole lot of compost out of it too! Usually the manure from the chickens raised on pasture goes straight onto the grass and builds top soil, to great effect. It is spread widely as the chickens move every day. But gathering the manure for compost means, in spring, we can plant out our veggies without having to buy in compost.

We usually use a deep litter system in our brooder where we lay out a thick layer of wood shavings for the first batch of the season, and keep adding to it during the course of their time in the brooder. Between batches we scrape a layer of shavings off, turn and moisten the shavings, and let it begin to decompose for a week before the next batch of chicks comes in. From the second batch of the season, the floor is warmer from the decomposition, and there is a certain level of microbes that are beneficial to the development of the new chicks (although we supplement with probiotics to keep them strong too). However, the wood shavings are not always ideal for using in compost. When the chicks are in the brooder, they are small and while they don’t really have a heavy manure load, it is important to keep their bedding dry and so the ratio of wood shavings to manure is low. These wood shavings are often pine too which can be too acidic for growing in. But we used a similar deep litter approach in the shed.

In these photos you can see the chickens in the shed, on their warm wood chips, a varied mix of wood from trees cut on the property.

(click pics to see more)

Lessons

The lessons we learnt in this were far more extensive than we had anticipated. While we know the pros and cons of free range and pasture raised systems, it becomes so real when you actually see it with your own eyes (and smell it with your own nose!).

Labour and Time

Firstly, raising chickens in a free range style it was a lot less labour intensive! We simply opened the curtains in the morning, and closed them at night. No moving fences, no pulling shelters around. The shed was close to the feed store, we could fill water tanks with a hose pipe instead of hauling tanks of water around. All in all, the time was drastically reduced. The downside of this is that because the daily chores can be done so quickly, there is a lot less time spent with the chickens and so observation was reduced.

Cost

Secondly, there were reduced costs in some ways, and higher costs in others. Obviously less labour time meant we were freed up for time spent on other tasks. The chickens seemed to grow a lot faster because they were less active and used less energy to keep themselves warm at night, and especially kept warm from the decomposing wood chips on the floor. By keeping heat lamps on at night, electricity usage was much higher. As a regenerative farm, we try to limit our buying in of resources and use as much as we can from our own land, and return as much as we can to the land. Having solar supplemented power meant much of this electricity came from the sun (stored in batteries for night time) but sometimes usage exceeds production. The other major input cost that was higher was the use of shavings. We usually only use wood shavings in the first three weeks in the brooder but now we needed to keep this large spacious shed dry at night too so we went through a lot of shavings, that were bought in.

Land Impact

Impact after just two successive batches of chickens in a free range model

The benefit to the land of pasture raised raised chickens cannot be emphasised enough. The spread of manure by moving chickens daily builds top soil and improves grass growth for each successive batch of chickens meaning better forage and organic matter on the land.

With this free range set up, obviously in our case the benefit is the delicious compost that comes out of it, with minimal effort because the chickens did all the work! However, the chickens had one large paddock of grass that they went out onto during the day. 300 chickens. All day, every day for weeks. Because this area can now rest after intensive use in our case, it should recover well. But if we were to continue to run batches here week after week after week, all year round, there would be no grass or forage left. After two batches of chickens, there was very little grass left. In all fairness, it is the deep of winter and the recovery of the grass is beyond slow. Perhaps in Summer it is better but we still couldn’t see how there wouldn’t be damage. The manure build up close to the doorways is extremely heavy and the impact on the grass is intense. Favourite dirt bath spots became craters. The same areas of grass would be grazed and damaged.

Chickens

The impact on the chickens is varied too. Our reasoning for this experiment is that the welfare of the animals is of utmost importance. Therefore, in the deep of winter, putting them in field pens straight after the brooder could be too much of a shock to the chickens.

Our first observation is that the chickens were obviously warmer and able to acclimatise slowly and successfully despite the freezing temperatures. After about a week in the indoor-outdoor shed, had it been warm enough, these chickens would have done fine in the field pen shelters. But their work on the compost was not yet done;) (And neither was our work on building winter pens!)

The chickens had access to heat lamps at night and sunshine during the day. We noticed though that for the first few days, none of the chickens ventured outside. In a pasture raised model, they are outside 24/7 so they automatically begin foraging, dirt bathing and eating grass. In the free range style, they really had to be encouraged. Because of the wood chips, we are confident they were getting forage by scratching in the compost (which chickens LOVE doing!) but whether this was comparable to being outside 24/7…?

The second observation was predators. It didn’t take long for the owls to figure out how to get in at night, and the birds of prey began circling during the day. In a pasture raised model, the chickens would be close to their shelters all the time so if a bird of prey flew over, they could seek cover. With this free range style, the chickens could venture far from the shed and end up being attacked as they couldn’t get back undercover quickly. Would they be likely to venture out again any time soon? A scarecrow was a quick, low-tech solution but the predator birds would probably wise up pretty quickly.

On the last night of the experiment, a mongoose or wild cat got into the shed too with massive loss. This animal had obviously been watching for a while and then figured out how to get in because the set up stayed the same.

So overall, as an experiment, it was incredibly useful for our learning, keeping chickens warm, and producing compost. For us, and our farm values, the pasture raised model is still preferable. We feel more empowered now to improve our pasture raised system as a result and have built new pens, are busy modifying our old pens and reassessing our land usage to better raise our chickens on pasture. The new pens will hopefully keep the chickens warmer and more protected as we expand onto flatter and further areas of the farm where predation risks are much higher. We will continue trying these new pens for the balance of winter rather than using this shed set up. Plus we got a ‘shed-load’ of great compost out of it too!

Keep following our blog for updates on our new field pens, and the veggie garden using this compost.

Delicious compost!